La cuarta edición del Festival de Cine Instar arrancó el lunes 4 de diciembre de 2023 en diversas sedes a lo largo del mundo y se desarrollará de forma híbrida hasta el 10 del mes en curso.

Más allá de lo complicada que suele ser la recepción de las producciones independientes al habitar en una zona de distribución casi residual, las películas de Instar padecen una presión extra debido al contenido explícito del mensaje que difunden. Presión que se explica, como viene sucediendo en los últimos años, a través de la censura, esa herramienta bochornosa tan afín a los Gobiernos totalitarios.

La torpe habilidad del Gobierno cubano, del Ministerio de Cultura (Mincult), de la Unión de Escritores y Artistas de Cuba (Uneac) y del Instituto Cubano de Arte e Industria Cinematográficos (Icaic) para atacar la producción independiente que se sale de los llamados parámetros revolucionarios logra aislar a los realizadores a tal punto que termina excluyéndolos e, incluso, sacándolos del país. Lo anterior, unido al fenómeno migratorio que sufre la sociedad cubana en la actualidad, ha afectado de manera notable la presencia de varios de los realizadores jóvenes en la isla. El Festival de Cine Instar ha logrado que la zona de exclusión se convierta en una oportunidad para que los proyectos no solo puedan reforzarse en el exilio, sino que expandan su mensaje desde el exterior.

Una de las particularidades de esta edición del festival tiene que ver precisamente con la extensión de las sedes y la participación de realizadores de países que también sufren bajo la sombra del totalitarismo de las dictaduras o de los Gobiernos autoritarios. Cortometrajes de Venezuela, Nicaragua, Irán y Haití compiten junto a producciones cubanas coproducidas en algunos casos en Estados Unidos, Italia, España, Canadá, Brasil y Argentina.

Las presentaciones de las películas y las actividades colaterales de Instar dispondrán de espacios físicos en varias ciudades en seis países. Barcelona, París, Nueva York, Miami, Ciudad de México, Buenos Aires y San Pablo albergarán la muestra. En Cuba, la experiencia del asedio gubernamental en la sede del Instituto de Artivismo «Hannah Arendt» (Instar) en La Habana durante la primera edición del festival en 2019, unido al funcionamiento del evento durante la pandemia de manera remota a través de Internet, ha convencido a los organizadores de la utilización de la plataforma Festhome para visionar la programación online de las películas, tanto de la muestra especial como de las obras que aparecen en concurso.

El cineasta José Luis Aparicio, que repite curaduría del festival en 2023, defiende la expansión del evento a partir de la expansión de una diáspora de realizadores que crece sin parar como consecuencia del accidente en que se ha convertido la vida de los cubanos: «¿No es acaso la nación una entidad más compleja que aquella que desmarcan los límites geográficos, los extremos políticos? ¿De qué manera repensar la estructura del festival para que refleje, e incluso potencie, la actual circunstancia de la gran mayoría de los cineastas que acompaña?».

Más allá de la lista de obras en concurso —que se analizan en este texto con más detenimiento—, no se debe perder la oportunidad de disfrutar de las presentaciones especiales del festival. La selección incluye películas de cineastas jóvenes como Miguel Coyula, Ricardo Figueredo, Rafael Ramírez, Alejandro Alonso y Marcel Beltrán ―estos dos últimos también con películas en concurso― junto a realizadores consagrados como Fernando y Miñuca Villaverde.

EN EL PRINCIPIO FUE LA CENSURA

Para comprender de una manera coherente los orígenes del festival habría que remontarse a 2018. En ese año, la feliz coincidencia de la muestra A Cuban Cinema Under Censureship —curada por el crítico Dean Luis Reyes— y la performance de la artista Tania Bruguera —Sin título (La Habana 2000)— en el MoMa de Nueva York terminó generando una serie de ideas que desembocarían en la aparición de la sección de cine dentro del Instituto de Artivismo «Hannah Arendt».

El objetivo de la sección era reubicar y dar visibilidad a cierto tipo de cineastas y películas que en Cuba no tenían opciones más allá de la producción independiente. Sin embargo, el proyecto de un festival de cine no se concretaría hasta un año después. Le precedería la creación del premio PM —un fondo de ayuda para óperas primas— y el premio Nicolás Guillén Landrián para obras en cualquier estado de producción. Después llegaría la Muestra de Cine Independiente-Pendiente, con curaduría de la escritora y actriz Lynn Cruz, antesala de lo que sería el Festival de Cine Instar en 2019.

La edición siguiente, curada por el cineasta José Luis Aparicio —que en lo adelante se encargaría de organizar el festival—, va a cubrir 2020 y 2021. El evento, con una cobertura virtual debido a las restricciones de la pandemia de la COVID-19, estaría marcado por la desaparición en Cuba de la Muestra Joven, consecuencia del recrudecimiento de la censura y la represión del régimen contra cualquier tipo de manifestación artística considerada contestataria.

En 2022, la muestra Land Without Images formó parte de Documenta 15 en Kassel, Alemania; un archivo que logró reunir más de 150 películas en un esfuerzo sin precedentes por recuperar parte de la historia audiovisual cubana, ocultada y secuestrada por la visión oficialista de la Revolución.

UNA LISTA OFICIAL CONTRA EL OFICIALISMO

Con el festival, Tania Bruguera y el resto de los organizadores persiguen extender la compleja y singular pauta fundacional del Instituto de Artivismo «Hannah Arendt» a la hora de aglutinar obras que se desarrollen en esa zona intermedia que existe entre la creación artística y el activismo. La fortaleza del tratamiento de la realidad podría explicar la preponderancia de los documentales sobre las obras de ficción en la lista oficial del evento.

Hay luego otro tipo de división que responde al diálogo que se establece con el espectador. No puede, o al menos no debe, enfrentarse asumiendo iguales variables de análisis ante películas como La opción cero de Marcel Beltrán (construida a partir de videos tomados con la cámara de varios móviles, en la que se sublima el rigor de la crudeza de una realidad que no quiere ser creativa, no quiere ambages, no los necesita), con películas como Mafifa de Daniela Muñoz (que, a pesar de estar filmada con un estilo aparentemente descuidado, el espectador termina por aceptar la narrativa de proximidad como un discurso que no está exento de belleza).

En La opción cero, Marcel logra transmitir el desasosiego de sus personajes porque de alguna forma todos sentimos que podríamos reproducir cada uno de sus estados de ánimo. Sabemos cómo de posible llega a ser la desesperación por dejar atrás el legado de las doctrinas, la falta de libertad, la impotencia, el hambre, el rencor, el cansancio y la tristeza vital que nos inoculó el dogma corrupto e insensible que significa la Revolución.

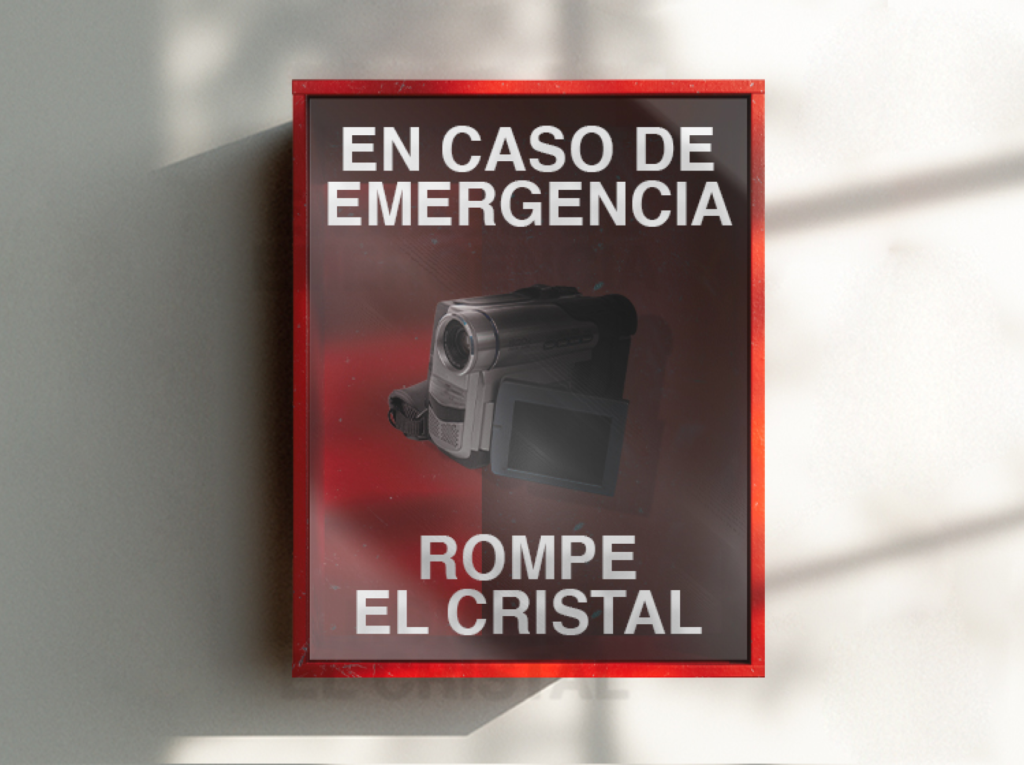

La travesía de La opción cero es el impulso último de un tipo de cubano que no pudo resolver de una manera más fácil el modo de largarse. Un tipo de cubano que quizá se sorprenda a sí mismo por su fortaleza y por su capacidad para mantenerse unido en los momentos más difíciles. Móvil en mano, grabando y haciendo directas en las redes sociales como única arma para seguir adelante.

El filme de Marcel es de las películas en las que, si hay alguna duda respecto a cómo concibe el cine su director, lo más aconsejable es revisar su filmografía. La opción cero no es un documental para hablar estrictamente de cine.

Sin abandonar el tema de la visión del inmigrante, nos encontramos con Un homme sous son influence. Se trata de un emigrante que está en otra condición, ha llegado, sufre por otras cosas. En la ficción de Enmanuel Martín hay una latencia tragicómica que es muy cómica. Por momentos quisieras ser un magnate y hacerle un mecenazgo para que produzca la película con más calma. No sé si para quitar los jump cuts que a lo mejor no son jump cuts o porque notas que el talento se disipa exclusivamente por un tema de velocidad en el rodaje.

El chucho que impone el punto de vista del director sobre el negacionismo, los gurús financieros, las estructuras piramidales, el trumpismo o el activismo desbordado de sus novias Nicole —que a pesar de su energía militante no tienen ni idea de lo qué pasa en Cuba—. A él le gustaría que para ellas Cuba fuera importante y le duele que no sea así. Sin embargo, cuando tiene que defenderse de su falta de compromiso se justifica argumentando que en Cuba había política a todas horas y en todas partes y por esa razón él no quiere saber nada de política.

Esta indolencia con la política te hace pensar que la pequeña patria de Enmanuel se parece a la de su amigo Carlos Melián cuando estaban en Santiago de Cuba. Preocupados por un cine menos social, con una proyección estética cuyas fuentes no tienen nada que ver con Cuba, más allá de la recuperación de Santiago como expresión de una conciencia territorial. La misma conciencia territorial que quizá Enmanuel haya trasladado a las ciudades canadienses que lo han acogido y con las que se siente en deuda por no poder estrenar en ellas su película.

En Llamadas desde Moscú de Luis A. Yero —última víctima de la censura al ser eliminada de la programación del Nuevo Festival de Cine Latinoamericano—, asistimos a una zona de desarraigo que no ha llegado a la de Enmanuel Martín en Un homme sous son influence. La performance de soledad de Yero establece una Cuba que funciona en la memoria de sus personajes como un amor tóxico al que sabes que no puedes volver. El vínculo que queda se explica todo el tiempo a través del móvil, con llamadas, con mensajes, con Tik Tok. Siempre encerrados, sea en la habitación, en el ascensor o en el metro. Los planos rodados en exterior funcionan como cortinillas para ordenar las tramas que se cruzan sin llegar a tocarse. El filme está envuelto en un ambiente que mezcla un tono de decadencia queer con la ciudad de Moscú como telón de fondo de un exagerado escenario distópico, acentuado por la banda sonora y las preocupaciones estereotipadas de la guerra.

Cuando uno de los personajes está hablando ―aclaro que por teléfono― con una amiga y le asegura que su etapa de estudiante fue la mejor época de sus vidas. No estamos en presencia ni de un lugar común ni de una reflexión de inmadurez. Es simplemente la constatación de una generación castrada, sin presente ni futuro.

Como ocurre con los primerísimos primeros planos de Mafifa o con la áspera sobriedad del segundo acto de Taxibol, terminamos claudicando positivamente con el tono narrativo de los diálogos monologuizados de los personajes, quienes teléfono en mano transmiten una melancolía que sabemos que no nació en Rusia. Tristeza de inmigrante que mira las noticias de su país en Meta, vaya o no vaya a volver.

En Los puros, Carla Valdés hace un delicado y escueto documental sobre la amistad de una generación que vivió los primeros años de adoctrinamiento de la Revolución con lastimosa inocencia. Sus padres y sus amigos quedan en una casa en la playa para celebrar el reencuentro. Cargados de recuerdos y reflexiones sobre cómo afrontaron —lo que bien hace en llamar uno de los personajes— el futuro.

Visitar la URSS y observar cómo el sistema se va quebrando lentamente les genera una decepción devastadora. El modelo no funciona, no sirve de nada tener fe en que algo cambie y, lo peor, es el mismo modelo de Cuba —no sirve de nada tener fe en que algo cambie—.

En Taxibol, Tommaso Santambrogio contrapone dos planos narrativos tan sólidos como diferentes. En el primero, con marcado carácter documental, rueda la conversación entre el cineasta filipino Lav Díaz y el taxista Gustavo Fleita en el interior de su taxi mientras recorren las calles de San Antonio de los Baños. El diálogo en dos idiomas, así como cierta atmósfera de amistosa condescendencia, va creando un extrañamiento dentro de la secuencia que se completa con la confesión violenta de Lav respecto a Juan Mijares, militar responsable de varios crímenes durante la dictadura de Ferdinando Marcos en Filipinas.

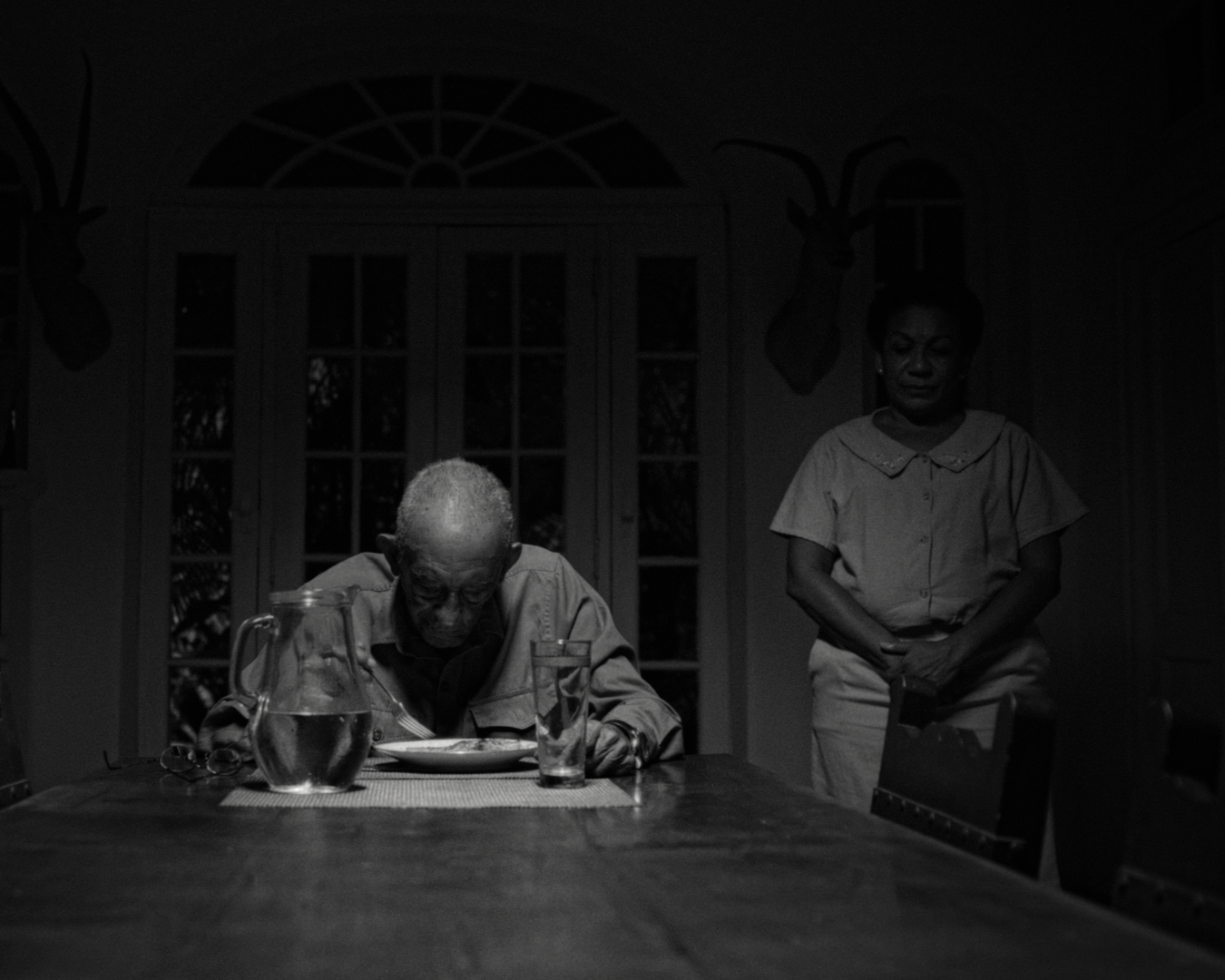

El segundo plano narrativo es un ejercicio de sobriedad cinematográfica en el que el actor Mario Limonta se echa sobre los hombros el tono de lo que resta de película. La representación tambaleante pero imponente del viejo asesino radicado en Cuba pone en relieve la práctica no poco numerosa de exmilitares de dictaduras, terroristas, antiguos nazis y demás calaña histórica afincados en países del tercer mundo para escapar de la justicia.

El baile de símbolos por el que arrastra los pies Juan Mijares a veces puede parecer simple, sobre todo, el que tiene que ver con las pesadillas que lo asaltan noche tras noche por la culpa o el terror de que lo ajusticien. Más logrados son los momentos en los que, a pesar de su edad, funge de matarife para sacrificar un cerdo —acercándonos al militar sanguinario que disfruta con la muerte— o la escena en la que utiliza el telescopio para mantener vigilados a sus hombres como si fuera un capataz que ronda a sus esclavos o un latifundista que no les quita ojo a sus ciervos o un comandante en jefe que no deja vivir a su pueblo.

Con Taxibol, Santambrogio logra que las imágenes adquieran el peso suficiente para quedarse en la memoria. En una de sus diatribas dentro del taxi, Lav Díaz manda al carajo el cine que se hace bajo la etiqueta del arte por el arte, declaración de intenciones que podría ponerle los pelos de punta al espectador o lanzarlo de cabeza a las barricadas. Lo bueno y, sobre todo, lo gratificante es que después del speech el segundo plano narrativo no renuncia a lo cinematográfico y logra un poso de ecuanimidad que le viene muy bien al final de la película.

El cortometraje Agwe, dirigido por Samuel Suffren, es la abanderada de las obras que conforman la lista oficial de películas que no son cubanas y una de las gratas sorpresas del festival. El pulso del filme abandona todo tipo de intelectualización a la hora de afrontar la necesidad de sus personajes. Aquí no hay discursos de género, inclusión o racismo estructural. Aquí hay pobreza. Los personajes se mueven en un límite que define la existencia como una manera cruda de subsistencia. La aldea de pescadores en la que viven anclados los protagonistas reconfigura el significado del mar como algo que va más allá de la fuente que les provee de vida. El mar es un tesoro porque es el mejor amigo de las fronteras —como reza la voz que se escucha en la primera escena de la película—, sus olas llevan esperanza.

Samuel Suffren logra condensar el tempo de la narración para que los 17 minutos de metraje alcancen para unificar los tres actos, para que la película respire e incluso sea emocionante. La puesta en escena añade un controlado movimiento dentro del plano, poniendo en valor un tipo de dirección que no deberíamos echar tanto en falta. El rigor parece ortodoxo, pero es correctísimo y el espectador agradece la fluidez de la narración. Luego está el compendio que ofrece la belleza de un tipo de cultura específica dentro de un paraje conmovedor y una historia desgarradora.

En El rodeo, de Carlos Melián, por momentos la recreación de las atmósferas parece serlo todo. Al leer la sinopsis se piensa que se entiende un poco más, pero en realidad el espectador se queda con la sensación de que necesitaría la sinopsis de la sinopsis. Lo bueno es que las pequeñas unidades de significación, al igual que en Abisal, parecen estrofas. Buenas estrofas. Bien escritas. Los diálogos son lo suficientemente sorprendentes como para sostener las pequeñas unidades de significación.

Lo malo es que al unirlo todo regresamos a la ambigüedad. En su Pierre Menard, autor del Quijote, Borges decía que la ambigüedad siempre es una riqueza. Aquí puede que lo sea porque es una película que te va sorprendiendo con las ocurrencias del director. Como la conversación de un amigo muy inteligente que te divierte con sus digresiones. Incluso lo que para cualquiera podría ser un símbolo quizá para él no lo sea. Ni la isla ni las jaulas ni el pueblo inundado ni la muerte. Todo es exactamente lo que es porque su visión se enrola mejor en un discurso del divertimento. Por eso El rodeo a veces parece un ejercicio. Que alguien le produzca un largo a Carlos Melián para que saque afuera todo lo que tiene que decir.

Con Abisal, de Alejandro Alonso, se completan las películas en concurso que podríamos llamar de autor. Si bien es cierto que las secuencias parecen también estrofas —como en el caso de Melián—, el discurso de Alejandro es más descarnado, más directo, menos territorial. La dirección de las escenas y el trabajo con los actores transmite un estado de comodidad difícil de explicar. Igual sucede con la fotografía. Si tuvieras un hijo que fuera una lata de celuloide se la dejarías con total confianza a Alejandro porque la convertiría con toda seguridad en una película hermosa.

Abisal, junto a Mafifa y la recién censurada Llamadas desde Moscú, son tres de las películas que fueron o han sido programadas por el Icaic. Abisal, incluso, obtuvo el Coral a mejor corto documental en 2022 en el Festival Internacional del Nuevo Cine Latinoamericano. El affaire con la oficialidad no terminó bien porque el mensaje que envió el director desde Madrid para ser difundido en la ceremonia de premiación fue censurado.

El tema de la censura, de leitmotiv a factor común de la historia amarga de la Revolución, catalizando obras que no tienen la más mínima oportunidad de distribuirse —como el periplo selvático de supervivencia de Marcel Beltrán, Veritas de Eliecer Jiménez o Mujeres que sueñan un país de Fernando Fraguela—. Lo anterior no quiere decir que el resto de las películas vayan a ser distribuidas por el Icaic. Aquí va censurado toʼ el mundo, Instar no es un Festival de películas censuradas, pero casi.

A Mujeres que sueñan un país le ocurre algo parecido a La opción cero respecto a la urgencia de la producción. Las salidas para documentar el encierro en la casa del artista Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara junto a otros miembros del Movimiento San Isidro (MSI) se limitan prácticamente a los archivos grabados por los teléfonos móviles de los acuartelados y las directas que fueron subiendo a las redes hasta viralizarse —como ocurrió después con el puño en alto del rapero Maykel Osorbo atado a una esposa policial—.

La batalla generada en los medios de comunicación oficiales cubanos versus la contundencia «contrahistórica» de lo que el mundo pudo observar en las redes fue determinante —en igual sentido, cómo olvidar el episodio de la versión ralentizada emitida por el Noticiero Nacional de Televisión sobre el golpe que lanzó Alpidio Alonso Grau, ministro de Cultura, para hacerle creer a la población que solamente intentaba estrechar la mano en señal de saludo—.

El uso de las redes antes y durante el acuartelamiento en San Isidro no solo fue decisivo como forma de extender la verdad, también funcionó como chispa para sacudir el posicionamiento de personas cuyas conciencias permanecían tan adoctrinadas que eran absolutamente apolíticas. Es el caso de Daniela Rojo, una de las voces que cohesionan el discurso de la película junto a Katherine Bisquet y a Anamely Ramos. En la película, Daniela admite despertar del letargo después de acceder a la información que se estaba vertiendo a raíz del Movimiento San Isidro, la consiguiente protesta ante el Mincult, la formación del grupo 27N, el estallido social del 11J y la marcha frustrada del 15N.

Mujeres que sueñan un país es un documental imprescindible sobre uno de los momentos más importantes de la historia reciente de Cuba. El núcleo de la película, sin embargo, transmite una autosuficiencia que no pareciera necesitar más punto de vista que el que define el acontecimiento histórico en sí. Sobre ese eje, pivota y se instala en la memoria sin la necesidad de un punto de vista que parece estar esperando una película que no es esta. Quizá el conflicto esté solo en el título. El enfoque del relato desde la óptica de Daniela, de Katherine y de Anamely por momentos se diluye ante la fortaleza social y audiovisual que arrojó el MSI, un fenómeno sin distinción de sexos, razas y credos que no se merece la excepcionalidad de ser soñado por ningún colectivo más allá del conjunto de todos los cubanos.

En Camino de lava, la directora Gretel Marín articula un discurso que no cesa. Es absolutamente respetable porque no solo reivindica, sino que desmiente falacias oficialistas como la ausencia de racismo en Cuba, así como las dificultades añadidas que sufren los colectivos racializados para abrirse paso en una sociedad que sigue sin sacudirse la lacra de los prejuicios. Asume también la representación de otro tipo de minorías como las personas homosexuales, ataca el patriarcado y defiende, quizá tangencialmente, el valor de protegerse ante la apropiación cultural. La cuestión es que el discurso sobrepasa los valores de la película por cuanto es película, porque depende más del valor del mensaje que está intentando transmitir que de otro tipo de sensibilidad.

En Mafifa, por otro lado, puede que se esté en presencia de una visión demasiado personal como para concebirla desde una dimensión sociológica. Sin embargo, la intención reivindicativa de Daniela Muñoz Barroso sobre la figura de Gladys termina tejiendo alrededor de la campanera una exaltación feminista, sin manejar otro discurso que la admiración sobre una mujer cuya memoria merece ser rescatada porque llegó a convertirse en leyenda dentro de los congueros de Santiago de Cuba, terreno de reconocido carácter patriarcal. El mensaje de esa reivindicación se transmite desde la autenticidad de las emociones que es capaz de transmitir el lenguaje del cine y no desde el efecto que pueda perpetrar la voz de un personaje que actúa como narrador de los problemas que le aquejan o pueden aquejarle como ocurre con los protagonistas de Camino de lava.

Lo inquietante y no menos curioso del proceso —que al final también podría entenderse como aculturación— es que el posicionamiento que se reconoce en Camino de lava es una herencia de las democracias occidentales, específicamente de las izquierdas progresistas en su búsqueda de un nuevo perfil de votante ante la crisis de la clase obrera como grupo social reconocible. En Cuba, al no haber una democracia y, por ende, una izquierda que necesite empoderarse, se termina sesgando aún más una sociedad que necesita estar unida sobre todas las cosas. Lo anterior sin contar que son prácticas de bandos políticos que por lo general ¡apoyan a la Revolución cubana! y que, por lo tanto, no reconocen la dictadura por ser una dictadura de izquierdas.

En el corto de animación Hojas de K, Gloria Carrión utiliza los dibujos personales de K para construir un retrato de la violencia de la dictadura en Nicaragua vista a través de la mirada de una adolescente. El abuso policial y el desparpajo de un Gobierno corrupto que ahonda en la herida de un país que se desangra va marcando el pulso de una historia que nos devuelve a una niña que no volverá a ser la misma después de la tortura y la cárcel.

Las otras dos películas extranjeras incluidas en la selección oficial del festival son And How Miserable is the Home of Evil del iraní Saleh Kashefi y Ventanas del venezolano Jhon Ciavaldini. El corto de Kashefi hace una arriesgada recreación de los últimos momentos de la caída del líder supremo Ali Khamenei, con una puesta en escena que recuerda más el espacio de un acto performativo que el de una película en sí.

Con Ventanas, Ciavaldini sumerge al espectador en un relato de desarraigo y violencia en la Venezuela de 2017, que es al mismo tiempo la Venezuela de Chávez y Maduro. Construido a partir de la comunicación con su madre desde el exilio en Buenos Aires y de videos tomados desde la distancia endeble de una ventana, el espectador asume la posición de un testigo que observa aterrado el horror de la represión bolivariana.

COMPOTAS PARA EL POSTRE

La inclusión del documental Veritas de Eliecer Jiménez en la selección oficial del festival ha acabado de agitar el avispero. La he dejado para el final porque de alguna forma simboliza el sentido más primario del Instituto de Artivismo «Hannah Arendt», el valor de sus miembros, sus colaboradores y fundadores.

Se trata de esas películas que te recuerdan la profundidad en la que una doctrina puede mantener enterrada tu mente. Mientras más profundo, más oscuro. Por eso muchas personas se sorprenden cuando descubren que en ese documental sobre Playa Girón el punto de vista es el de los cubanos de carne, hueso y alma que conocimos como «los mercenarios». Hombrecitos disfrazados de camuflaje. Torpes, cobardes y fáciles de apresar. Caminando en fila, cabizbajos como si hubieran nacido para la derrota.

Cuando Eliécer Jiménez concibió la película sabía que tocaba uno de los temas más delicados de la historia de la Revolución. También debió intuir que tenía entre manos un tema de gran interés. Más allá de la luz que se pueda arrojar a partir de los testimonios de los veteranos entrevistados, la película funciona incluso sin proyectarse. Fue lo que sucedió en las horas previas a la inauguración del IV Festival de Cine Instar, por el revuelo que está causando entre la cúpula del Estado cubano, como evidencian los respectivos tuits del ministro de Cultura Alpidio Alonso y de Abel Prieto.

«¿En nombre de qué libertad, a no ser la de destruir la Revolución, puede pedirse que nos entendamos con quienes hacen parte de esta nueva operación pagada por la CIA contra el proyecto colectivo del pueblo cubano? ¿Qué patriota podría llamar nuestro al cine contrarrevolucionario?», escribió Alonso Grau.

«Otra operación a gran escala vs. la cultura revolucionaria: el Festival de Cine Instar. Una vez más pretenden dinamitar la institucionalidad cultural con el empleo de “líderes” pagados por nuestros enemigos. Nos subestiman nuevamente», escribió Prieto.

Viendo las reacciones, la verdad es que no sé por qué el Gobierno no acaba de explotar el negocio de fiscalizar con algún impuesto la lista interminable de asalariados que tiene en nómina la CIA dentro y fuera del país.

Veritas, un reposado pero emocional relato de algunos de los miembros de la Brigada 2506, desgrana el proceso de la preparación, el entrenamiento y la llegada a las costas cubanas, así como la decisiva influencia de J. F. Kennedy en el fracaso de la operación.

El testimonio de los veteranos de Bahía de Cochinos se va reconstruyendo en el espectador con la amargura del que se siente traicionado. Una amargura que se acrecienta por la vulnerabilidad del que actúa por sentimientos que pueden confundirse con la inocencia. Por eso duele cuando esos hombres reconocen que han sido abandonados a su suerte. Saben que no van a ganar y se enfrentan a un destino totalmente incierto.

En aquel momento nos enseñaron que fueron cambiados por compotas.

Si nos atenemos a la historia, tanto para ellos como para nosotros, la elipsis no solo ha sido más cruel, también está siendo mucho más larga.